How Long Do Ice Ages Last

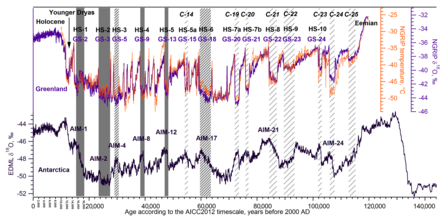

Chronology of climatic events of importance for the terminal glacial menstruum (about the last 120,000 years)

The Last Glacial Period (LGP), also known colloquially as the last water ice age or simply water ice historic period,[1] occurred from the end of the Eemian to the end of the Younger Dryas, encompassing the menstruum c. 115,000 – c. 11,700 years ago. The LGP is part of a larger sequence of glacial and interglacial periods known as the 4th glaciation which started effectually ii,588,000 years agone and is ongoing.[2] The definition of the Fourth every bit beginning 2.58 meg years agone (Mya) is based on the formation of the Arctic ice cap. The Antarctic ice canvass began to class earlier, at almost 34 Mya, in the mid-Cenozoic (Eocene–Oligocene extinction event). The term Late Cenozoic Ice Age is used to include this early stage.[three]

During this terminal glacial flow, alternate episodes of glacier advance and retreat occurred. Inside the last glacial period, the Last Glacial Maximum was approximately 22,000 years agone. While the general blueprint of global cooling and glacier accelerate was similar, local differences in the development of glacier advance and retreat brand comparison the details from continent to continent difficult (see picture of ice cadre data below for differences). Around 12,800 years ago, the Younger Dryas, the most recent glacial epoch, began, a coda to the preceding 100,000-twelvemonth glacial period. Its end most xi,550 years ago marked the get-go of the Holocene, the current geological epoch.

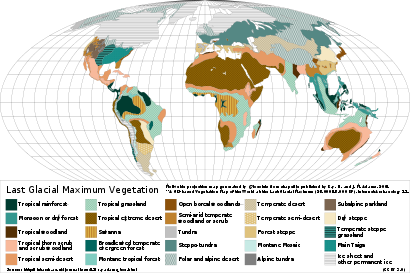

From the indicate of view of human archaeology, the LGP falls in the Paleolithic and early Mesolithic periods. When the glaciation event started, Human sapiens was bars to lower latitudes and used tools comparable to those used by Neanderthals in western and central Eurasia and by Denisovans and Homo erectus in Asia. About the stop of the event, H. sapiens migrated into Eurasia and Commonwealth of australia. Archaeological and genetic data suggest that the source populations of Paleolithic humans survived the LGP in sparsely wooded areas, and dispersed through areas of high primary productivity, while fugitive dense forest cover.[four]

Artist'due south impression of the terminal glacial menses at glacial maximum[5]

Origin and definition [edit]

The LGP is oft colloquially referred to every bit the "concluding water ice age", though the term ice age is not strictly divers, and on a longer geological perspective, the final few 1000000 years could be termed a single water ice age given the continual presence of ice sheets near both poles. Glacials are somewhat better divers, every bit colder phases during which glaciers accelerate, separated by relatively warm interglacials. The end of the last glacial period, which was about ten,000 years ago, is oftentimes called the end of the water ice historic period, although all-encompassing year-circular water ice persists in Antarctica and Greenland. Over the past few million years, the glacial-interglacial cycles have been "paced" past periodic variations in the Earth's orbit via Milankovitch cycles.

The LGP has been intensively studied in North America, northern Eurasia, the Himalayas, and other formerly glaciated regions effectually the world. The glaciations that occurred during this glacial period covered many areas, mainly in the Northern Hemisphere and to a bottom extent in the Southern Hemisphere. They accept different names, historically developed and depending on their geographic distributions: Fraser (in the Pacific Cordillera of Due north America), Pinedale (in the Fundamental Rocky Mountains), Wisconsinan or Wisconsin (in central North America), Devensian (in the British Isles),[6] Midlandian (in Ireland), Würm (in the Alps), Mérida (in Venezuela), Weichselian or Vistulian (in Northern Europe and northern Central Europe), Valdai in Russia and Zyryanka in Siberia, Llanquihue in Republic of chile, and Otira in New Zealand. The geochronological Belatedly Pleistocene includes the late glacial (Weichselian) and the immediately preceding penultimate interglacial (Eemian) catamenia.

Overview [edit]

Northern Hemisphere [edit]

Canada was about completely covered by water ice, every bit was the northern part of the United states of america, both blanketed by the huge Laurentide Ice Canvass. Alaska remained mostly ice gratis due to arid climate conditions. Local glaciations existed in the Rocky Mountains and the Cordilleran ice sheet and equally ice fields and ice caps in the Sierra Nevada in northern California.[7] In Britain, mainland Europe, and northwestern Asia, the Scandinavian ice sail once again reached the northern parts of the British Isles, Germany, Poland, and Russia, extending as far due east as the Taymyr Peninsula in western Siberia.[eight] The maximum extent of western Siberian glaciation was reached by well-nigh 18,000 to 17,000 BP, thus afterward than in Europe (22,000–xviii,000 BP)[9] Northeastern Siberia was not covered by a continental-calibration ice sheet.[10] Instead, large, but restricted, icefield complexes covered mountain ranges within northeast Siberia, including the Kamchatka-Koryak Mountains.[xi] [12]

The Chill Ocean between the huge water ice sheets of America and Eurasia was not frozen throughout, but similar today, probably was covered merely past relatively shallow ice, subject to seasonal changes and riddled with icebergs calving from the surrounding ice sheets. According to the sediment composition retrieved from abyssal cores, even times of seasonally open waters must have occurred.[13]

Outside the main ice sheets, widespread glaciation occurred on the highest mountains of the Alpide belt. In contrast to the earlier glacial stages, the Würm glaciation was composed of smaller water ice caps and mostly confined to valley glaciers, sending glacial lobes into the Alpine foreland. Local ice fields or small ice sheets could exist constitute capping the highest massifs of the Pyrenees, the Carpathian Mountains, the Balkan mountains, the Caucasus, and the mountains of Turkey and Iran.[14]

In the Himalayas and the Tibetan Plateau, in that location is bear witness that glaciers advanced considerably, particularly betwixt 47,000 and 27,000 BP,[15] but the exact ages,[16] [17] as well as the germination of a single contiguous ice canvas on the Tibetan Plateau, is controversial.[18] [xix] [20]

Other areas of the Northern Hemisphere did not bear all-encompassing ice sheets, only local glaciers were widespread at loftier altitudes. Parts of Taiwan, for case, were repeatedly glaciated between 44,250 and 10,680 BP[21] every bit well as the Japanese Alps. In both areas, maximum glacier advance occurred between 60,000 and 30,000 BP.[22] To a withal bottom extent, glaciers existed in Africa, for example in the High Atlas, the mountains of Morocco, the Mountain Atakor massif in southern People's democratic republic of algeria, and several mountains in Ethiopia. Just southward of the equator, an ice cap of several hundred square kilometers was present on the due east African mountains in the Kilimanjaro massif, Mountain Republic of kenya, and the Rwenzori Mountains, which notwithstanding bear relic glaciers today.[23]

Southern Hemisphere [edit]

Glaciation of the Southern Hemisphere was less all-encompassing. Water ice sheets existed in the Andes (Patagonian Water ice Canvas), where half dozen glacier advances between 33,500 and thirteen,900 BP in the Chilean Andes take been reported.[24] Antarctica was entirely glaciated, much like today, but different today the ice canvas left no uncovered area. In mainland Commonwealth of australia only a very modest surface area in the vicinity of Mount Kosciuszko was glaciated, whereas in Tasmania glaciation was more widespread.[25] An ice sheet formed in New Zealand, covering all of the Southern Alps, where at least three glacial advances can be distinguished.[26] Local water ice caps existed in the highest mountains of the island of New Guinea, where temperatures were 5 to half-dozen° C colder than at present.[27] [28] The principal areas of Papua New Guinea where glaciers developed during the LGP were the Central Cordillera, the Owen Stanley Range, and the Saruwaged Range. Mountain Giluwe in the Cardinal Cordillera had a "more than or less continuous ice cap covering about 188 kmii and extending down to 3200-3500 m".[27] In Western New Republic of guinea, remnants of these glaciers are withal preserved atop Puncak Jaya and Ngga Pilimsit.[28]

Modest glaciers developed in a few favorable places in Southern Africa during the terminal glacial period.[29] [A] [B] These modest glaciers would have been located in the Kingdom of lesotho Highlands and parts of the Drakensberg.[31] [32] The evolution of glaciers was likely aided in part due to shade provided by next cliffs.[32] Various moraines and former glacial niches have been identified in the eastern Lesotho Highlands a few kilometres west of the Great Escarpment, at altitudes greater than 3,000 yard on south-facing slopes.[31] Studies suggest that the annual average temperature in the mountains of Southern Africa was about 6°C colder than now, in line with temperature drops estimated for Tasmania and southern Patagonia during the same time. This resulted in an environment of relatively barren periglaciation without permafrost, but with deep seasonal freezing on south-facing slopes. Periglaciation in the eastern Drakensberg and Lesotho Highlands produced solifluction deposits and blockfields; including blockstreams and rock garlands.[29] [30]

Deglaciation [edit]

Scientists from the Middle for Chill Gas Hydrate, Environment and Climate at the University of Tromsø, published a report in June 2017[33] describing over a hundred ocean sediment craters, some iii,000 m wide and upwards to 300 grand deep, formed by explosive eruptions of methyl hydride from destabilized methane hydrates, following water ice-sheet retreat during the LGP, around 12,000 years ago. These areas around the Barents Bounding main still seep marsh gas today. The written report hypothesized that existing bulges containing methane reservoirs could eventually have the same fate.

Named local glaciations [edit]

Antarctica [edit]

During the final glacial flow, Antarctica was blanketed past a massive water ice canvass, much equally it is today; however, the ice covered all land areas and extended into the ocean onto the eye and outer continental shelf.[34] [35] Counterintuitively though, co-ordinate to ice modeling done in 2002, water ice over primal Eastward Antarctica was generally thinner than it is today.[36]

Europe [edit]

Devensian and Midlandian glaciation (Britain and Ireland) [edit]

British geologists refer to the LGP as the Devensian. Irish gaelic geologists, geographers, and archaeologists refer to the Midlandian glaciation, as its effects in Ireland are largely visible in the Irish gaelic Midlands. The name Devensian is derived from the Latin Dēvenses, people living past the Dee (Dēva in Latin), a river on the Welsh border near which deposits from the period are particularly well represented.[37]

The effects of this glaciation can exist seen in many geological features of England, Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland. Its deposits have been found overlying material from the preceding Ipswichian stage and lying beneath those from the post-obit Holocene, which is the current stage Tis is sometimes called the Flandrian interglacial in Britain.

The latter part of the Devensian includes pollen zones I–IV, the Allerød oscillation and Bølling oscillation, and the Oldest Dryas, Older Dryas, and Younger Dryas common cold periods.

[edit]

Europe during the last glacial menses

Culling names include: Weichsel glaciation or Vistulian glaciation (referring to the Polish River Vistula or its German name Weichsel). Prove suggests that the water ice sheets were at their maximum size for only a short period, betwixt 25,000 and thirteen,000 BP. Eight interstadials accept been recognized in the Weichselian, including the Oerel, Glinde, Moershoofd, Hengelo, and Denekamp; however, correlation with isotope stages is still in procedure.[38] [39] During the glacial maximum in Scandinavia, only the western parts of Jutland were ice-complimentary, and a big part of what is today the North Ocean was dry land connecting Jutland with Great britain (come across Doggerland).

The Baltic Body of water, with its unique brackish h2o, is a result of meltwater from the Weichsel glaciation combining with saltwater from the Due north Sea when the straits betwixt Sweden and Denmark opened. Initially, when the ice began melting almost x,300 BP, seawater filled the isostatically depressed expanse, a temporary marine incursion that geologists dub the Yoldia Bounding main. And so, as postglacial isostatic rebound lifted the region nigh 9500 BP, the deepest bowl of the Baltic became a freshwater lake, in palaeological contexts referred to every bit Ancylus Lake, which is identifiable in the freshwater fauna found in sediment cores. The lake was filled by glacial runoff, but as worldwide body of water level continued ascent, saltwater over again breached the sill about 8000 BP, forming a marine Littorina Sea, which was followed past another freshwater phase earlier the present brackish marine organisation was established. "At its present state of evolution, the marine life of the Baltic Sea is less than about 4000 years old", Drs. Thulin and Andrushaitis remarked when reviewing these sequences in 2003.

Overlying ice had exerted pressure on the Earth's surface. As a issue of melting ice, the land has continued to rise yearly in Scandinavia, mostly in northern Sweden and Finland, where the land is ascension at a charge per unit of as much as 8–9 mm per yr, or ane one thousand in 100 years. This is important for archaeologists, since a site that was coastal in the Nordic Stone Age now is inland and can exist dated by its relative distance from the present shore.

Würm glaciation (Alps) [edit]

Violet: extent of the Tall ice canvass in the Würm glaciation. Blue: extent in earlier ice ages.

The term Würm is derived from a river in the Alpine foreland, roughly mark the maximum glacier accelerate of this particular glacial menstruation. The Alps were where the first systematic scientific research on water ice ages was conducted by Louis Agassiz at the kickoff of the 19th century. Here, the Würm glaciation of the LGP was intensively studied. Pollen assay, the statistical analyses of microfossilized plant pollens constitute in geological deposits, chronicled the dramatic changes in the European surround during the Würm glaciation. During the summit of Würm glaciation, c. 24,000 – c. 10,000 BP, most of western and central Europe and Eurasia was open up steppe-tundra, while the Alps presented solid ice fields and montane glaciers. Scandinavia and much of Britain were under water ice.

During the Würm, the Rhône Glacier covered the whole western Swiss plateau, reaching today's regions of Solothurn and Aarau. In the region of Bern, it merged with the Aar glacier. The Rhine Glacier is currently the subject of the virtually detailed studies. Glaciers of the Reuss and the Limmat advanced sometimes as far equally the Jura. Montane and piedmont glaciers formed the land past grinding away virtually all traces of the older Günz and Mindel glaciation, by depositing base moraines and last moraines of dissimilar retraction phases and loess deposits, and by the proglacial rivers' shifting and redepositing gravels. Beneath the surface, they had profound and lasting influence on geothermal heat and the patterns of deep groundwater flow.

Due north America [edit]

Pinedale or Fraser glaciation (Rocky Mountains) [edit]

The Pinedale (central Rocky Mountains) or Fraser (Cordilleran ice sheet) glaciation was the last of the major glaciations to announced in the Rocky Mountains in the United States. The Pinedale lasted from around xxx,000 to 10,000 years ago, and was at its greatest extent between 23,500 and 21,000 years ago.[twoscore] This glaciation was somewhat distinct from the main Wisconsin glaciation, as it was only loosely related to the giant ice sheets and was instead equanimous of mountain glaciers, merging into the Cordilleran ice canvass.[41] The Cordilleran water ice sheet produced features such equally glacial Lake Missoula, which broke complimentary from its ice dam, causing the massive Missoula Floods. USGS geologists guess that the cycle of flooding and reformation of the lake lasted an average of 55 years and that the floods occurred about 40 times over the 2,000-yr menses starting 15,000 years ago.[42] Glacial lake outburst floods such as these are not uncommon today in Iceland and other places.

Wisconsin glaciation [edit]

The Wisconsin glacial episode was the final major advance of continental glaciers in the North American Laurentide water ice canvass. At the height of glaciation, the Bering state bridge potentially permitted migration of mammals, including people, to North America from Siberia.

It radically altered the geography of Northward America n of the Ohio River. At the height of the Wisconsin episode glaciation, ice covered most of Canada, the Upper Midwest, and New England, equally well as parts of Montana and Washington. On Kelleys Isle in Lake Erie or in New York'south Primal Park, the grooves left past these glaciers can be hands observed. In southwestern Saskatchewan and southeastern Alberta, a suture zone between the Laurentide and Cordilleran ice sheets formed the Cypress Hills, which is the northernmost point in North America that remained south of the continental ice sheets.

The Neat Lakes are the result of glacial scour and pooling of meltwater at the rim of the receding ice. When the enormous mass of the continental water ice sheet retreated, the Keen Lakes began gradually moving south due to isostatic rebound of the north shore. Niagara Falls is as well a product of the glaciation, equally is the class of the Ohio River, which largely supplanted the prior Teays River.

With the help of several very broad glacial lakes, it released floods through the gorge of the Upper Mississippi River, which in turn was formed during an earlier glacial menstruation.

In its retreat, the Wisconsin episode glaciation left terminal moraines that class Long Island, Cake Island, Cape Cod, Nomans Land, Martha's Vineyard, Nantucket, Sable Island, and the Oak Ridges Moraine in due south-central Ontario, Canada. In Wisconsin itself, information technology left the Kettle Moraine. The drumlins and eskers formed at its melting edge are landmarks of the lower Connecticut River Valley.

Tahoe, Tenaya, and Tioga, Sierra Nevada [edit]

In the Sierra Nevada, three stages of glacial maxima (sometimes incorrectly chosen water ice ages) were separated by warmer periods. These glacial maxima are chosen, from oldest to youngest, Tahoe, Tenaya, and Tioga.[43] The Tahoe reached its maximum extent perhaps about 70,000 years ago. Piddling is known near the Tenaya. The Tioga was the least severe and final of the Wisconsin episode. Information technology began about 30,000 years ago, reached its greatest advance 21,000 years ago, and ended about 10,000 years ago.

Greenland glaciation [edit]

In northwest Greenland, ice coverage attained a very early maximum in the LGP around 114,000. After this early maximum, ice coverage was similar to today until the end of the last glacial period. Towards the stop, glaciers avant-garde over again before retreating to their present extent.[44] According to ice cadre data, the Greenland climate was dry during the LGP, with atmospheric precipitation reaching perhaps simply 20% of today's value.[45]

South America [edit]

Mérida glaciation (Venezuelan Andes) [edit]

Map showing the extent of the glaciated area in Venezuelan Andes during the Mérida glaciation

The name Mérida glaciation is proposed to designate the alpine glaciation that affected the primal Venezuelan Andes during the Late Pleistocene. 2 chief moraine levels have been recognized - 1 with an elevation of 2,600–two,700 m (8,500–8,900 ft), and another with an elevation of 3,000–3,500 m (9,800–eleven,500 ft). The snowfall line during the terminal glacial advance was lowered approximately 1,200 grand (3,900 ft) beneath the present snow line, which is 3,700 k (12,100 ft). The glaciated area in the Cordillera de Mérida was about 600 kmtwo (230 sq mi); this included these high areas, from southwest to northeast: Páramo de Tamá, Páramo Batallón, Páramo Los Conejos, Páramo Piedras Blancas, and Teta de Niquitao. Around 200 km2 (77 sq mi) of the total glaciated area was in the Sierra Nevada de Mérida, and of that amount, the largest concentration, 50 km2 (19 sq mi), was in the areas of Pico Bolívar, Pico Humboldt [4,942 m (16,214 ft)], and Pico Bonpland [4,983 m (16,348 ft)]. Radiocarbon dating indicates that the moraines are older than x,000 BP, and probably older than 13,000 BP. The lower moraine level probably corresponds to the main Wisconsin glacial advance. The upper level probably represents the final glacial advance (Late Wisconsin).[46] [47] [48] [49] [fifty]

Llanquihue glaciation (Southern Andes) [edit]

The Llanquihue glaciation takes its name from Llanquihue Lake in southern Republic of chile, which is a fan-shaped piedmont glacial lake. On the lake's western shores, large moraine systems occur, of which the innermost belong to the LGP. Llanquihue Lake's varves are a node signal in southern Chile's varve geochronology. During the last glacial maximum, the Patagonian ice canvass extended over the Andes from about 35°S to Tierra del Fuego at 55°S. The western part appears to have been very active, with wet basal weather condition, while the eastern part was common cold-based. Cryogenic features such as ice wedges, patterned ground, pingos, rock glaciers, palsas, soil cryoturbation, and solifluction deposits developed in unglaciated extra-Andean Patagonia during the last glaciation, but not all these reported features take been verified.[51] The area west of Llanquihue Lake was water ice-free during the last glacial maximum, and had sparsely distributed vegetation dominated by Nothofagus. Valdivian temperate rain forest was reduced to scattered remnants on the western side of the Andes.[52]

Modelled maximum extent of the Antarctic water ice sheet 21,000 years earlier present

Encounter also [edit]

| Region | Glacial i | Glacial 2 | Glacial 3 | Glacial 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alps | Günz | Mindel | Riss | Würm |

| North Europe | Eburonian | Elsterian | Saalian | Weichselian |

| British Isles | Beestonian | Anglian | Wolstonian | Devensian |

| Midwest U.Due south. | Nebraskan | Kansan | Illinoian | Wisconsinan |

- Glacial history of Minnesota

- Glacial lake outburst flood

- Glacial period

- Penultimate Glacial Period

- Pleistocene, which includes:

- Pleistocene megafauna

- Plio-Pleistocene

- Quaternary extinction event

- Quaternary glaciation

- Ocean level ascent

- Stone Historic period

- Timeline of glaciation

- Valparaiso Moraine

Notes [edit]

- ^ Prior to the 2010s, considerable argue arose on whether Southern Africa was glaciated during the last glacial cycle or not.[29] [30]

- ^ The former existence of large glaciers or deep snow cover over much of the Lesotho Highlands has been judged unlikely because the lack of glacial morphology (e.g. rôche moutonnées) and the being of periglacial regolith that has not been reworked by glaciers.[30] Estimates of the mean annual temperature in Southern Africa during the last glacial maximum indicate the temperatures were not low enough to initiate or sustain a widespread glaciation. The former existence of rock glaciers or large glaciers is, according to the same written report, ruled out, because of a lack of conclusive field evidence and the implausibility of the 10–17°C temperature drop, relative to the present, that such features would imply.[29]

References [edit]

- ^ "The history of water ice on World". New Scientist . Retrieved February 17, 2022.

- ^ Clayton, Lee; Attig, John W.; Mickelson, David M.; Johnson, Marking D.; Syverson, Kent M. "Glaciation of Wisconsin" (PDF). Dept. Geology, University of Wisconsin.

- ^ Academy of Houston–Clear Lake – Disasters Class Notes – Chapter 12: Climate Change sce.uhcl.edu/Pitts/disastersclassnotes/chapter_12_Climate_Change.doc

- ^ Gavashelishvili, A.; Tarkhnishvili, D. (2016). "Biomes and human distribution during the concluding ice age". Global Ecology and Biogeography. 25 (5): 563–574. doi:10.1111/geb.12437.

- ^ Crowley, Thomas J. (1995). "Ice age terrestrial carbon changes revisited". Global Biogeochemical Cycles. 9 (3): 377–389. Bibcode:1995GBioC...9..377C. doi:10.1029/95GB01107.

- ^ Catt, J. A.; et al. (2006). "Fourth: Ice Sheets and their Legacy". In Brenchley, P. J.; Rawson, P. F. (eds.). The Geology of England and Wales (2nd ed.). London: The Geological Society. pp. 451–52. ISBN978-1-86239-199-iv.

- ^ Clark, D.H. Extent, timing, and climatic significance of latest Pleistocene and Holocene glaciation in the Sierra Nevada, California (PDF 20 Mb) (Ph.D.). Seattle: Washington University.

- ^ Möller, P.; et al. (2006). "Severnaya Zemlya, Arctic Russia: a nucleation area for Kara Ocean ice sheets during the Middle to Late Quaternary" (PDF eleven.5 Mb). 4th Science Reviews. 25 (21–22): 2894–2936. Bibcode:2006QSRv...25.2894M. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2006.02.016.

- ^ Matti Saarnisto: Climate variability during the final interglacial-glacial cycle in NW Eurasia. Abstracts of PAGES – PEPIII: Past Climate Variability Through Europe and Africa, 2001 Archived April 6, 2008, at the Wayback Motorcar

- ^ Gualtieri, Lyn; et al. (May 2003). "Pleistocene raised marine deposits on Wrangel Isle, northeast Siberia and implications for the presence of an East Siberian ice sheet". Quaternary Enquiry. 59 (3): 399–410. Bibcode:2003QuRes..59..399G. doi:ten.1016/S0033-5894(03)00057-7. S2CID 58945572.

- ^ Ehlers, Gibbard & 2004 Three, pp. 321–323

- ^ Barr, I.D; Clark, C.D. (2011). "Glaciers and Climate in Pacific Far NE Russia during the Last Glacial Maximum" (PDF). Journal of Fourth Science. 26 (2): 227. Bibcode:2011JQS....26..227B. doi:10.1002/jqs.1450.

- ^ Spielhagen, Robert F.; et al. (2004). "Chill Sea deep-sea record of northern Eurasian ice sheet history". Quaternary Science Reviews. 23 (xi–13): 1455–83. Bibcode:2004QSRv...23.1455S. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2003.12.015.

- ^ Williams, Jr., Richard South.; Ferrigno, Jane Thousand. (1991). "Glaciers of the Center East and Africa – Glaciers of Turkey" (PDF 2.5 Mb). U.s.a.Geological Survey Professional person Paper 1386-G-1.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

Ferrigno, Jane Yard. (1991). "Glaciers of the Middle East and Africa – Glaciers of Iran" (PDF 1.25 Mb). U.Southward.Geological Survey Professional Paper 1386-G-2. - ^ Owen, Lewis A.; et al. (2002). "A annotation on the extent of glaciation throughout the Himalaya during the global Last Glacial Maximum". 4th Scientific discipline Reviews. 21 (1): 147–157. Bibcode:2002QSRv...21..147O. doi:x.1016/S0277-3791(01)00104-4.

- ^ Kuhle, M., Kuhle, S. (2010): Review on Dating methods: Numerical Dating in the Quaternary of High Asia. In: Journal of Mount Science (2010) vii: 105–122.

- ^ Chevalier, Marie-Luce; et al. (2011). "Constraints on the late 4th glaciations in Tibet from cosmogenic exposure ages of moraine surfaces". Fourth Science Reviews. 30 (five–6): 528–554. Bibcode:2011QSRv...30..528C. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2010.xi.005.

- ^ Kuhle, Matthias (2002). "A relief-specific model of the ice age on the footing of uplift-controlled glacier areas in Tibet and the corresponding albedo increase every bit well equally their positive climatological feedback past means of the global radiation geometry". Climate Research. 20: 1–7. Bibcode:2002ClRes..20....1K. doi:x.3354/cr020001.

- ^ Ehlers, Gibbard & 2004 III, Kuhle, Yard (August 31, 2011). "The High Glacial (Terminal Water ice Age and LGM) ice cover in High and Central Asia". Fourth Glaciations - Extent and Chronology. pp. 175–199. ISBN9780444534477.

- ^ Lehmkuhl, F. (2003). "Die eiszeitliche Vergletscherung Hochasiens – lokale Vergletscherungen oder übergeordneter Eisschild?". Geographische Rundschau. 55 (two): 28–33. Archived from the original on July 7, 2007. Retrieved Feb 9, 2008.

- ^ Zhijiu Cui; et al. (2002). "The Quaternary glaciation of Shesan Mountain in Taiwan and glacial classification in monsoon areas". Fourth International. 97–98: 147–153. Bibcode:2002QuInt..97..147C. doi:x.1016/S1040-6182(02)00060-5.

- ^ Yugo Ono; et al. (September–Oct 2005). "Mountain glaciation in Japan and Taiwan at the global Last Glacial Maximum". 4th International. 138–139: 79–92. Bibcode:2005QuInt.138...79O. doi:ten.1016/j.quaint.2005.02.007.

- ^ Young, James A.T.; Hastenrath, Stefan (1991). "Glaciers of the Center East and Africa – Glaciers of Africa" (PDF 1.25 Mb). U.Southward. Geological Survey Professional Paper 1386-One thousand-3.

- ^ Lowell, T.Five.; et al. (1995). "Interhemisperic correlation of belatedly Pleistocene glacial events" (PDF ii.3 Mb). Science. 269 (5230): 1541–49. Bibcode:1995Sci...269.1541L. doi:x.1126/science.269.5230.1541. PMID 17789444. S2CID 13594891.

- ^ Ollier, C.D. "Australian Landforms and their History". National Mapping Fab. Geoscience Commonwealth of australia. Archived from the original on Baronial 8, 2008.

- ^ Burrows, C. J.; Moar, Northward. T. (1996). "A mid Otira Glaciation palaeosol and flora from the Castle Hill Bowl, Canterbury, New Zealand" (PDF). New Zealand Journal of Botany. 34 (iv): 539–545. doi:ten.1080/0028825X.1996.10410134. Archived from the original (PDF 340 Kb) on February 27, 2008.

- ^ a b Löffler, Ernst (1972). "Pleistocene glaciation in Papua and New Guinea". Zeitschrift für Geomorphologie. Supplementband 13: 32–58.

- ^ a b Allison, Ian; Peterson, James A. (1988). Glaciers of Irian Jaya, Indonesia: Ascertainment and Mapping of the Glaciers Shown on Landsat Images. ISBN978-0-607-71457-ix. U.Due south. Geological Survey professional paper 1386.

- ^ a b c d Mills, South.C.; Barrows, T.T.; Telfer, Chiliad.W.; Fifield, L.K. (2017). "The cold climate geomorphology of the Eastern Cape Drakensberg: A reevaluation of by climatic atmospheric condition during the concluding glacial bike in Southern Africa". Geomorphology. 278: 184–194. Bibcode:2017Geomo.278..184M. doi:x.1016/j.geomorph.2016.xi.011.

- ^ a b c Sumner, P.D. (2004). "Geomorphic and climatic implications of relict openwork block accumulations near Thabana-Ntlenyana, Kingdom of lesotho". Geografiska Annaler: Series A, Concrete Geography. 86 (3): 289–302. doi:ten.1111/j.0435-3676.2004.00232.ten. S2CID 128774864.

- ^ a b Mills, Stephanie C.; Grab, Stefan W.; Rea, Brice R.; Farrow, Aidan (2012). "Shifting westerlies and precipitation patterns during the Late Pleistocene in southern Africa determined using glacier reconstruction and mass remainder modelling". Quaternary Science Reviews. 55: 145–159. Bibcode:2012QSRv...55..145M. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2012.08.012.

- ^ a b Hall, Kevin (2010). "The shape of glacial valleys and implications for southern African glaciation". South African Geographical Journal. 92 (ane): 35–44. doi:ten.1080/03736245.2010.485360. hdl:2263/15429. S2CID 55436521.

- ^ "Similar 'champagne bottles being opened': Scientists document an aboriginal Arctic marsh gas explosion". The Washington Mail. June 1, 2017.

- ^ Anderson, J. B.; Shipp, Due south. S.; Lowe, A. L.; Wellner, J. Due south.; Mosola, A. B. (2002). "The Antarctic Ice Sheet during the Last Glacial Maximum and its subsequent retreat history: a review". Fourth Scientific discipline Reviews. 21 (ane–iii): 49–70. Bibcode:2002QSRv...21...49A. doi:10.1016/S0277-3791(01)00083-Ten.

- ^ Ehlers, Gibbard & 2004 Iii, Ingolfsson, O. Quaternary glacial and climate history of Antarctica (PDF). pp. iii–43.

- ^ Huybrechts, P. (2002). "Bounding main-level changes at the LGM from ice-dynamic reconstructions of the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets during the glacial cycles" (PDF). Quaternary Science Reviews. 21 (1–3): 203–231. Bibcode:2002QSRv...21..203H. doi:10.1016/S0277-3791(01)00082-eight.

- ^ OED

- ^ Behre Karl-Ernst, van der Plicht Johannes (1992). "Towards an absolute chronology for the concluding glacial menstruation in Europe: radiocarbon dates from Oerel, northern Germany" (PDF). Vegetation History and Archaeobotany. 1 (2): 111–117. doi:ten.1007/BF00206091. S2CID 55969605.

- ^ Davis, Owen One thousand. (2003). "Non-Marine Records: Correlations with the Marine Sequence". Introduction to Quaternary Ecology. University of Arizona. Archived from the original on July 27, 2017.

- ^ "Brief geologic history". Rocky Mountain National Park. Archived from the original on May 15, 2006.

- ^ "Ice Age Floods". U.South. National Park Service.

- ^ Waitt, Jr., Richard B. (Oct 1985). "Example for periodic, jumbo jökulhlaups from Pleistocene glacial Lake Missoula". Geological Society of America Bulletin. 96 (10): 1271–86. Bibcode:1985GSAB...96.1271W. doi:10.1130/0016-7606(1985)96<1271:CFPCJF>ii.0.CO;2.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ehlers, Gibbard & 2004 II, p. 57

- ^ Funder, Svend"Belatedly Quaternary stratigraphy and glaciology in the Thule area, Northwest Greenland". MoG Geoscience. 22: 63. 1990. Archived from the original on June half-dozen, 2007.

- ^ Johnsen, Sigfus J.; et al. (1992). "A "deep" ice cadre from East Greenland". MoG Geoscience. 29: 22. Archived from the original on June 6, 2007.

- ^ Sánchez Dávila, Gabriel (2016). "La Sierra de Santo Domingo: "Biogeographic reconstructions for the 4th of a former snowy mount range"" (in Castilian). doi:ten.13140/RG.2.2.21325.38886/i.

- ^ Schubert, Carlos (1998). "Glaciers of Venezuela". Usa Geological Survey (USGS P 1386-I).

- ^ Schubert, C.; Valastro, Southward. (1974). "Late Pleistocene glaciation of Páramo de La Culata, north-key Venezuelan Andes". Geologische Rundschau. 63 (ii): 516–538. Bibcode:1974GeoRu..63..516S. doi:x.1007/BF01820827. S2CID 129027718.

- ^ Mahaney, William C.; Milner, One thousand.W., Kalm, Volli; Dirsowzky, Randy W.; Hancock, R.G.5.; Beukens, Roelf P. (April one, 2008). "Testify for a Younger Dryas glacial accelerate in the Andes of northwestern Venezuela". Geomorphology. 96 (ane–2): 199–211. Bibcode:2008Geomo..96..199M. doi:10.1016/j.geomorph.2007.08.002.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Maximiliano, B.; Orlando, G.; Juan, C.; Ciro, S. "Glacial 4th geology of las Gonzales bowl, páramo los conejos, Venezuelan andes".

- ^ Trombotto Liaudat, Darío (2008). "Geocryology of Southern South America". In Rabassa, J. (ed.). The Late Cenozoic of Patagonia and Tierra del Fuego . pp. 255–268. ISBN978-0-444-52954-one.

- ^ Adams, Jonathan. "South America during the last 150,000 years". Archived from the original on January 30, 2010.

Further reading [edit]

- Bowen, D.Q. (1978). Quaternary geology: a stratigraphic framework for multidisciplinary piece of work. Oxford Uk: Pergamon Press. ISBN978-0-08-020409-3.

- Ehlers, J.; Gibbard, P. L., eds. (2004). Quaternary Glaciations: Extent and Chronology 2: Part Ii North America. Amsterdam: Elsevier. ISBN978-0-444-51462-2.

- Ehlers, J.; Gibbard, P. Fifty., eds. (2004). Quaternary Glaciations: Extent and Chronology 3: Part Iii: South America, Asia, Africa, Australia, Antarctica. Amsterdam: Elsevier. ISBN978-0-444-51593-3.

- Gillespie, A. R., Porter, S. C.; Atwater, B. F. (2004). The Quaternary Flow in the United States [of America]. Developments in Fourth Scientific discipline. Vol. 1. Amsterdam: Elsevier. ISBN978-0-444-51471-four.

{{cite volume}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Harris, A. Grand.; Tuttle, East.; Tuttle, Due south. D. (1997). Geology of National Parks (5th ed.). Iowa: Kendall/Hunt. ISBN978-0-7872-5353-0.

- Kuhle, Yard. (1988). "The Pleistocene Glaciation of Tibet and the Onset of Ice Ages – An Autocycle HypothesisGeoJournal". GeoJournal. 17 (iv): 581–596. doi:10.1007/BF00209444. S2CID 129234912.

- Mangerud, J.; Ehlers, J.; Gibbard, P., eds. (2004). 4th Glaciations : Extent and Chronology 1: Office I Europe. Amsterdam: Elsevier. ISBN978-0-444-51462-2.

- Sibrava, V.; Bowen, D.Q; Richmond, One thousand. M. (1986). "Quaternary Glaciations in the Northern Hemisphere". Fourth Science Reviews. 5: one–514. doi:10.1016/S0277-3791(86)80002-six.

- Pielou, Due east. C. (1991). After the Water ice Age : The Return of Life to Glaciated Due north America. Chicago IL: University Of Chicago Press. ISBN978-0-226-66812-iii.

External links [edit]

- Pielou, E. C. Later on the Water ice Historic period: The Render of Life to Glaciated North America (University of Chicago Press: 1992)

- National Atlas of the The states: Wisconsin Glaciation in North America: Present country of noesis

- Ray, Due north.; Adams, J.M. (2001). "A GIS-based Vegetation Map of the World at the Last Glacial Maximum (25,000–15,000 BP)" (PDF). Net Archaeology. eleven.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Last_Glacial_Period

Posted by: robertsontheind.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How Long Do Ice Ages Last"

Post a Comment